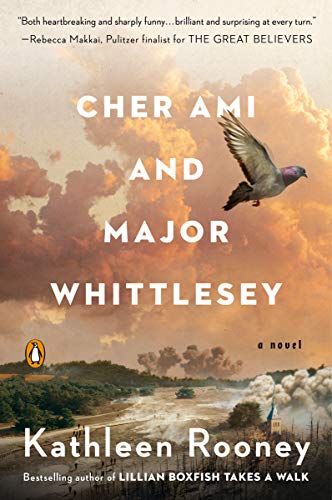

Cher Ami and Major Whittlesey: A novel by Kathleen Rooney

Penguin Random House, August 2020

366 pages, buy-link

A series of thin, alternating layers held together by a social gloop that looks like frosting, tastes like frosting, but the sweetness is too sweet and the cake that looks like cake and tastes like cake is little more than a story spoonfed to the hungry to make them think it all tastes good. This metaphor doesn’t describe Kathleen Rooney’s book, Cher Ami and Major Whittlesey—the book itself is good—but it does describe the content and the way Rooney forks that cake over to the reader, asking them to consider that gloop, to move it around on their plates and pay attention to the consistency, taste, and the layers underneath. The gloop, since you’re wondering, is the more insidious moral underpinnings of war and human society.

The story is conveyed through alternating chapters from the perspective of Cher Ami and Major Whittlesey (Whit), both fighting for the U.S. army in one of WWI’s largest battles, and often relays the same events through each character’s eyes. Whit is a human; Cher Ami is a homing pigeon. Eventually, the story culminates in Cher Ami saving Whit’s troops from the German military and friendly fire—don’t worry, this isn’t a spoiler, the events of the war aren’t what this book is about.

As a bird-lit enthusiast, I especially liked the nuggets of homing pigeon facts scattered throughout, like the fact that pigeons make a milky substance in their throats to feed their chicks—both parents do, or that pigeons have three eyelids and one set is basically the equivalent of windshield wipers. Look up pictures of both and you’ll keep these lil facts in your brain for ever and ever.

At times, reading from the pigeon perspective feels cheesy and the social commentary from the objective eyes of a bird can be a bit forced and occasionally pedantic. But there’s a reason for it, it causes the reader to examine the similarities and differences between animals and humans in war, and it evokes a common rhetorical device used after the Great War—the dead speaking from the grave (Cher Ami narrates from her perch in the Smithsonian). Make it make sense, and it’s an easy thing to get past.

The strength of this book is its existence at all. It’s hard to write a war novel that will appeal to a queer left-leaning femme (me) and keep her engaged til the end. The secret? Don’t glorify bloodshed, talk about the intense emotions produced by war, war propaganda, power dynamics, discussions of human and animal rights, disability justice, mental health, and queerness, etc., etc. Basically, don’t write a “war novel.” Rooney did just this, keeping true to the actual events that took place and embellishing upon historian’s theories, while filling in the narrative gaps with fictional rich social commentary and characters, making the book a sort of modern/historical war novel.

On that note, as a queer person, this book is a seed filling a gaping hole in literature that I’ve felt for years: historical fiction centering queer characters where angst around their queerness isn’t central to their story or the sole important part of their identity. Ideally, these characters will lead full lives that celebrate their queerness in a reimagining of history, throwing out the trope of forbidden love and identity crises in favor of a pure pleasure read where the only difference is Mr. Darcy is a Miss. Maybe this genre should live more in the realm of fantasy so as to not erase the resilience of real queer people of the past, but I still love to see it. Anyway, this book isn’t that soft beckoning glow from the heavens, but it’s certainly a seed and I’m more than happy to be the soil and the water. Just know that the pigeon is gay and deals with constant misgendering in a world where she doesn’t even care about gender—we’re on our way.

In short, the gloop in Rooney’s book is good gloop: refreshing, thought-provoking, a seed for past-obsessed queers, well-researched, and an homage to the animals humans have forced into war to meet their own ends.